Floating in space, a witch performs her daily search for meaning, and finds a future that must be subverted.

Published . 3459 words.

The dice were meant to be used for storytelling and creative exercises, but there were some obvious benefits to using them to plan the day’s activities. When the witch and her belle lived mostly alone on a bubble-island in the planet’s geostationary rubble belt, it helped to have a way of randomizing the day-to-day activities that kept their bubble of space habitable and hospitable.

That’s what her belle thought.

The witch knew the dice held portents.

The dice dated back to well before the witch had found her belle and moved into the bubble-island they shared. At the time she bought the dice, the witch had been living in a three-legged hut that wandered through a planet’s ring system, always in microgravity. The smith who had forged the dice for her had made them magnetic so they could be rolled on — tossed at — any sufficiently attractive surface. Their cold iron construction was expensive, but conveniently free from magical interference. The dice were free from meddling, free from anything that wasn’t mundane physics.

In the Baba Yaga hut, she had used to toss them along the surface of the stove.

In space, woodburning stoves made no sense, but the hut’s designers had built the hut’s air conditioning machinery into the shape of a freestanding stove for skeuomorphic affect, made of steel-clad ceramic panels that were ludicrously ill-suited to the idea of an air-conditioning unit, but perfectly suited to the idea of an old wood stove. The dice would tumble parallel to its surface, gradually drawn in by the magnetic interaction. Sometimes the a/c’s fan motors’ fields would kick a die across the room. Sometimes the die bounced off the wall, and sometimes it stuck. She had always regarded that far-flung die as the most significant of that day’s cast.

Today, in the pseudogravity afforded by the bubble-island, the dice clattered across the wooden kitchen table.

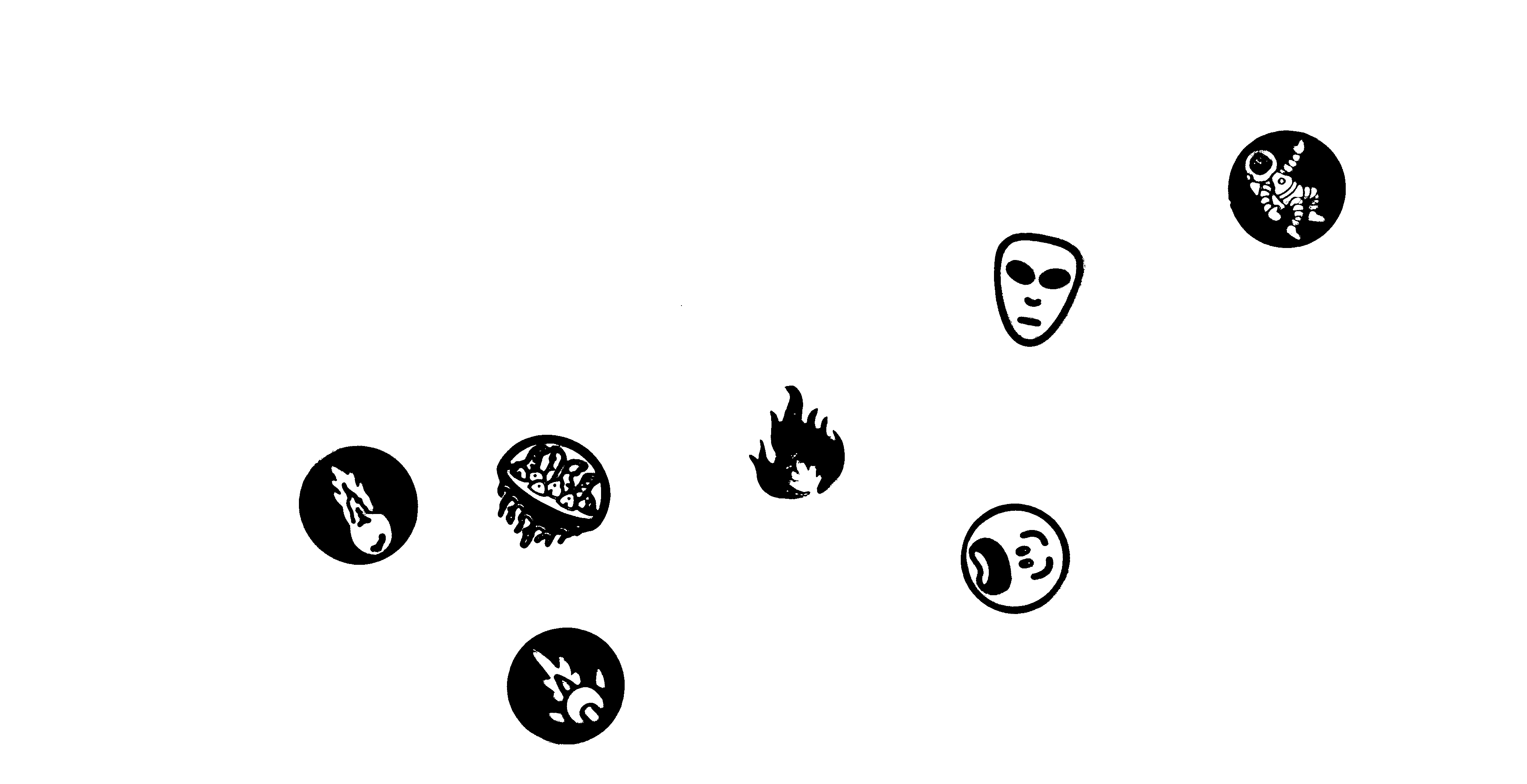

Each face of each die was a different icon; a full accounting of their faces would last for more pages than this story should hold. O Reader, pay attention to the dice as the witch does, and look not at the faces that are concealed but the ones that are revealed.

The bubble-island.

A domesticated fire.

A meteor.

The other meteor, in a different shape.

A spacesuited human, against a starry background.

The mask, somewhere between Tragedy and Comedy in its dour presentation.

The Scream.

Not an auspicious cast. It could easily be read as the end of the bubble-island and a disastrous end for all concerned. But the cast was also not a cast that could not be subverted.

The rest of the dice scattered farther across the table, landing in positions of irrelevance against the morning’s breakfast dishes.

Quickly the witch set to work.

While the witch prepares, observe the stage this scene plays out upon.

The witch used to live alone in a Baba Yaga hut. The hut was three rooms, by design convention stacked atop each other despite the hut’s native microgravity. When there is no pull towards any surface, no downwards acceleration, no weight, the orientation of surfaces is based on convention. In the hut, down was the direction of the floor. Thus the office and sleeping room became upladder. The utility room with racks of supplies and machinery and the airlock became downladder. In between was the room that held the kitchen, stove, table, cupola, and most of the plants.

The hut strode through the planet’s rubble-rings on three legs, slowly climbing the everlasting staircase as it kicked debris into lower garbage orbits or higher refinery orbits. Debris in eccentric lower orbits would gradually aerobrake and burn up in the planet’s atmosphere. The higher orbits were patrolled by recyclers whose gaping maws consumed all they encountered. Policing the orbits was not the witch’s duty, but it was how her house earned its keep.

Every so often the mail would be delivered by the mailman in his steam-puffing runabout, and with the mailman’s deliveries came the feedstocks that the hut could not refine on its own. This was the age of miracles and wonder, of fully automated luxury gay space communism, of post-scarcity resource allocation — yet resources still had to be distributed. Soon, there would be free energy, and with that, free matter. Not this decade, but next decade, for sure. By the end of the century at most.

Such things had been said for centuries.

When the witch retired for the second time, she pooled her resources with her belle and they acquired the bubble-island in its geostationary orbit.

Her hut was pleased to take up residence on the bubble-island, and to subsume its systems into the bubble-island’s own. It gained better radiators, better collectors, bigger materials stocks, and a biosphere that was bigger than the contents of the fridge and toilet. It could open its windows, grow a real porch, and begin to think about growing a dedicated bedroom.

Sure, the hut lost its independence. It no longer lived in full sunshine, where it could keep its solar wings always in the light. It now relied on the island’s own solar arrays and power banks. It no longer had control of its interior atmosphere, now obeying the island’s commands. Its feedstock containers were drained into the island’s own before being recycled. The island’s assembler consented to moving into the hut as a replacement for the hut’s outdated one.

The less said about what happened with the hut’s three legs when the hut merged with the island, the better.

For the witch, the real benefit of the bubble-island was being able to sleep outside.

The belle and the witch, snuggled in a pile of blankets. In the months that they had decided were winter, they pointed the bubble-island’s crystal dome away from the Sun at night, and watched the stars. In the summer months, the dome faced the planet, and they tracked the changes on the planet’s face as their ancestors had tracked the constellations. In the liminal months, the bubble changed from planet-facing to space-facing, or vice versa, in ways that brought the sun streaming over the island’s little horizon at a seasonal time.

It was a peaceful retirement from active duty, yet not one detached from the problem that had brought their different lives to this sphere.

The witch’s subversion of the day’s cast would take all day. Subversions of horrible futures usually did.

She cleared away the breakfast dishes, fed the bioreactor, watered the morning plants, fetched a sack of flour from the stores for her belle’s breadmaker. As her belle worked the mixer, they watched the cat disappear off the bubble-island’s horizon, and speculated where the cat’s travels would lead that day.

Eventually the witch climbed the ladder to her office, tucked away their sleeping cushions, and brought up the communications interface.

The first task was to arrange a meteor shower.

The planet was generally quiescent, as far as orbital activities went. Occasionally a rocket would be launched, or a new orbit-capable gun tested, and the watchers on high would have to intervene.

During the last major period of planetary activity, those in orbit had improved their countermeasures. The snag-and-drag missile system had been a resource-intensive but effective way to drop orbital aspirants back into the planet’s atmosphere. The intercepting snagger probes were able to latch on to 99.4% of rising material, deploying drag surfaces to brake the aspirant materiel, letting gravity pull the forbidden payloads back down to the surface.

To prevent planetary contamination by orbital society’s higher technology, the snag-and-drag missile system was as low-tech as possible. Self-destruct mechanisms built to slag and frag the probes during reentry ensured that no tech from the orbital watchers would fall into planetary hands.

But as with all good solutions, better solutions were found.

The chemical rockets of the snag-and-drag missiles were replaced by ballistic launch systems in higher orbits. The probes’ complex reaction control system thrusters were replaced by simple blocks of ablative cladding on the outside of the probe, vaporized by orbital lasers to adjust the probes’ trajectories towards their targets. These reductions in probe complexity decreased the cost, and spurred development of more-capable steering lasers until it no longer made sense to use snag probes.

The lasers and their descendents handled deceleration directly. The night skies of the planet were less often lit by the pinprick detonations of the snag-and-drag probes’ slag-and-frags, and more often lit by energetic reentries of burnt-out debris.

In the cat-and-mouse game of planetary launches vs orbital launch control, the balance adjusted more heavily in favor of launch control.

Still, the planetary launchers were known to be experimental at times, and for that reason some chemical-fueled snag-and-drag missiles were kept on duty. Their attendants kept the missiles ready for the day when the ground would send skywards a probe that could not be effectively pushed with photons.

These attendants tended to appreciate the chemical solutions to life’s problems. Of course the witch had worked with them. What, after all, is the difference between a witch’s brew and a rocket scientist’s propellant?

One of the witch’s friends was a missileer whose appreciation for missile displays had transcended duty to become a hobby. The two vocateurs talked friendliness and talked shop and talked about the weather. They bantered in the well-worn grooves of a habitual friendship. They traded favors. Certain things were put in motion, in ways metaphorical and physical.

This call concluded, the witch called another friend in a similar position. But instead of calling a third, she went about smoothing the way for the missileers’ actions with the launch control coordinators. Here was where her old skills stretched and limbered, baring a sweet smile at the labyrinthine bureaucratic beast.

In between calls, she printed off some new artwork for the toilet wall.

The version of Munch's The Scream that the witch hung on the wall above the reclaimer.

Then, it was time for the tedious tasks: airing out the spacesuits and mainlining some old Greek plays.

Subversions such as the witch would pull require a certain amount of sacrifice, and it was with repressed cringe that she pulled up a recording from her younger years, where the theatre troupe had decided to speed-run the Dionysia in a family-friendly way by fusing the comedy, the tragedy, and the tragicomedy.

They were not playwrights; their understanding of the source works was eh.

The play was bad. As bad as a gallon of milk left in the beach sun on a tropical island for a week. This must be distinctly understood, or nothing wonderful would follow from the witch’s watching.

With one eye on her younger self’s amateur acting, she worked her way down the checklists for the maintenance of her spacesuit, and her belle’s spacesuit, and the pack of emergency spacesuits, and her cat’s spacesuit.

Three

tedious

hours

later, she paused the play at its intermission and went in search of food, which she found in her belle’s arms in the kitchen.

Together they watched the horizon as the cat returned, spotted black fur becoming distinct from the background stars. The cat was wearing a flower crown that was prrrrobably woven by the crèche children who lived in a geostationary habitat fifteen degrees prograde. The cat roamed. Sometimes that meant field trips.

And then she returned to the spacesuits, to finish the four

remaining

hours’

work.

With grave and serious purpose, she donned each suit, and ran them through pressure cycles in the airlock. For a time, she borrowed her cat’s body to test the cat’s suit. There were things of fit that the cat considered important, but which the cat never deigned to complain about. The witch had learned to feel those problems with her own fur. When the cat’s spacesuit was once again clean and fitted, it went back on the rack with the rest.

When all the checklist items were checked, she stepped out the lock door with her broom, and flew over to the nearest rock.

On the rock’s vacuum-harsh faces grew patches of green-grey fuzz. They were a friend’s project, which she was taking notes on. The lichen did not appear to have changed — indeed, she would have been surprised if they had, since their life cycle was so slow — but she finger-danced through the items on the observation checklist all the same. The measurements confirmed that the lichen had not changed.

The one rest she allowed herself this day was to look at the arc of the planet beneath her feet, as her broom puffed away from the neighbor rock.

As big as a soccer ball held at the end of her arm, the sunlit half of the planet showed a blue-white marble much like her home planet. She could see the winds of a hurricane in the tropics, of a sou’easter off the largest continent, the brightness of the planet’s polar ice caps.

She spun the broom to bring the planet level with her eyes, and tilted her hat to block the daylight gleam. Even worn over a spacesuit, the wide-brimmed, conical black hat of her vocation stayed with her. She was a witch, and there were standards to be maintained.

The planet’s night side glowed blue with the light of the planetary inhabitants. On land and on sea, in the tropics and as far as the poles, the lights of civilization beat back the cold darkness of a moonless night sky. The lights were so bright that, according to the spies, the wan light of the planet’s rings could not be seen from the ground on any but the clearest night sky.

Perhaps the planetary occupants did not want to be reminded of the rings of rubble and wreckage, the remnants of a time when they held power beyond their own planet. Their exercise of that power had cost them dearly: they were not to be allowed back into space. Not this century. Maybe next century. We’ll see.

The witch sighed, and returned to the hut’s airlock, where the spacious comforts of the bubble-island were tainted by the waiting final act of the comedy-tragedy-tragicomedy.

When the suits were finally stowed, and the Chorus’ last line waveringly pronounced, the witch walked out the hut’s front door into the bubble-island’s greenery.

However big you may think it is, the answer is that a bubble-island is as big as it is needed to be. Where sufficiently analyzed magic met sufficiently advanced technology, the island reshaped itself to fit the needs of its occupants.

This bubble-island was built to appear flat, with the smallest of hills supporting a mixed-fruit tree above the fish pond. Flat paddies of wheat and rice stepped across the island, following the stream that issued from the pond. A small variable rock wall hid behind the tree’s hill, and a selection of newts, salamanders, frogs, toads, turtles, bats, and insects sang as dusk approached.

Between the hut and the dock was a gravel path, which in its meanderings went past the firepit by the shore. The cat brushed between the witch’s ankles as she walked down the path. It bounced ahead a few paces, stopped to catch the witch’s eye, and then bounded off through the fields to the edge of the bubble, and disappeared into the starry depths beyond.

Fire and closed ecologies do not, as a rule, mix. Fire has been one of the longest-feared tools of humanity, yet tonight the witch would wake its wild ways for the evening’s experience. She reached into the firepit, unplugged and removed the fake fire. It ran on ran on light and fans and flickering streamers of steam.

Tonight, the witch needed a real fire.

She tucked the false fire away in the basement of the hut. From behind the tree on the hill she drew her wrought-iron tripod and cauldron. Like her hat, the witch kept her cauldron in a visible place. Other people would store their cookware elsewhere, but a witch’s cauldron serves purposes beyond cooking.

There was no firewood stacked in this arcology; the witch did not particularly care about the lack of fuel. She was a witch.

Earlier in the day, while waiting on hold with the bureaucracy, she’d asked the fabber to print some logs. Simple carbohydrate and water matrices with aromatic compounds and a dash of fire retardant, that’s all. A simple enough spell.

Now she started the fire with a word, a lighter, and scraps of shredded letters. The island in reaction pushed just a little more oxygen to the pit, to prevent smouldering, and increased the breeze across the bubble to draw the fire’s emissions more quickly through the filters. The witch tsked as the fire wavered, heat stolen by the breeze, and repositioned herself to better shield the fire. The flames steadied, and swelled.

With the first log on the fire, she returned to the hut to retrieve the rest of dinner’s ingredients. It was stew night, which the cat apparently knew. The witch looked out the kitchen window as she pulled vegetables from the crisper, and saw the cat emerge from the starry background of the island’s border, carrying a fresh rabbit.

When the rabbits were cleaned and the stew well on its way, the witch set the sleeping hammock near the fire. She pulled blankets from the hut’s office-bedroom, and pulled her belle away from her work down to the shore.

Together they supped soup, and broke the belle’s morning bread to sop their bowls, and laughed around the day’s tasks, and pet the cat when the cat came for a fair share of the meal, and teased flowers with their toes as they lay back in the hammock.

Above them, the first meteoritic streaks of trashed orbital debris flashed through the planet’s atmosphere, like fireworks celebrating the longest day of summer.